To the soft sound of violin concertos, an elite team of long-distance racers relax after their recent race from Mesquite, Nevada to Bozeman—a 600-mile journey. Their lineage includes American war heroes and some of the best racers in Slovakia.

The team is a 150-strong roost of pigeons, under the watchful leadership of Dušan Smetana.

“ It's just amazing how one pound of feathers, bones, and meat can find it’s home after 15 hours and 600 miles,” Dušan said.

Dušan has been racing pigeons in Bozeman for about 20 years, but has had a love for the birds since his childhood in Slovakia.

“If you as an immigrant, you leave your old home behind you, you leave lots of things. Your family, your friends, your hobbies, traditions, you know, cuisines, everything,” Dušan said. “And then you're trying to maybe find those things in your new home. And I guess pigeons are one of them.”

Dušan’s pigeons just finished their racing season with the Western Open from Nevada. Racing pigeons can get pretty technical. Since they are only able to fly back to their home roost, racers drive their birds however far away, in this case, 600 miles, and release their birds from there. Then, the winner is decided by calculating yards per minute.

Pigeon races often happen through regional clubs. It makes it easier to race when all the lofts are generally in the same place. But these clubs are somewhat few and far between and more so as time goes on.

“There were lots of people racing 20 years ago. It's declining due to people not having time or so much entertainment from their phones or tablets, but maybe we'll hit a cycle. Maybe we'll get back again,” Dušan said.

The Bridger Mountain Racing Pigeon Club, the club Dušan races in, turned 29 in May. A decade after it started, Dusan rooted himself in the local pigeon racing scene by building his own loft.

The van-sized wooden loft is carefully designed. There’s a room for the young trainees, getting full at the time — Dušan’s pigeons hatch around April. And another room where 15 pairs of his retired champions breed the next line.

“ Some of the best pigeons, they finish the race seasons and they've been racing for three, four, five years. They're gonna be moving to breeding loft and hope they'll breed something as good as they are or better.”

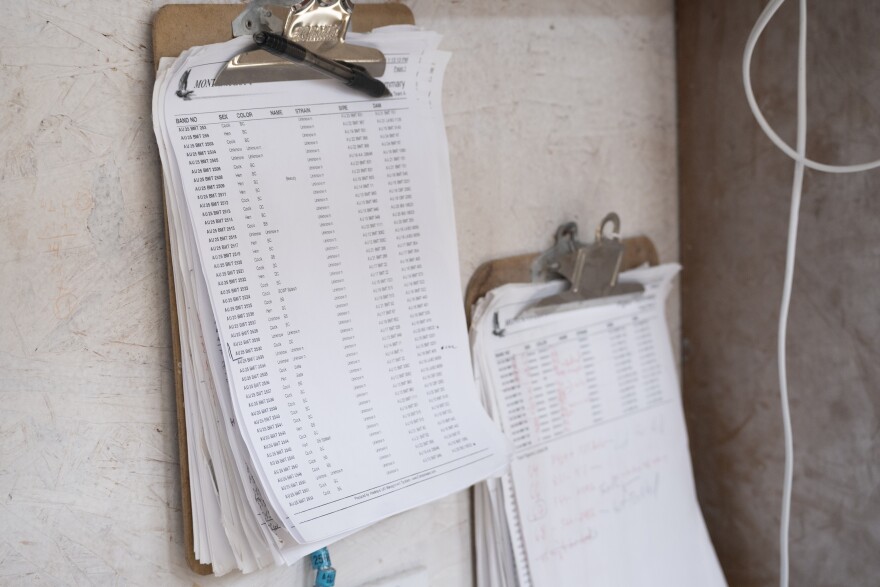

A clipboard hangs outside with detailed descriptions of each bird and notes of what pairs might produce the most successful babies. Next to the clipboard, a shelf full of supplements and medicine. Some designed for pigeons, some not. One bottle was iron-rich supplements for horses.

In fact, the whole place almost looked like a stable for football-sized racehorses. It’s kind of par for the course.

“It is basically like horse racing, but they call it ‘poor man’s race horsing,’” Dušan said.

His birds are the product of thousands of years of evolution. Their hearts are twice the size of a wild bird’s. Their sleek slate-gray coats and iridescent purple neck feathers are evidence of Dusan’s attentive feeding and care.

“We have to know which grain to give at which times, there's a bunch of grains mixed together. Corn, peas, wheat, barley, safflower, milo, hemp.”

There’s conflicting ideas on when humans first started domesticating pigeons — one of the first prominent documented cases was Egypt’s Pharaoh Ramesses III, who may have used the birds to communicate around 1150 B.C. Others argue Egyptians were using pigeons 200 years before that, and some estimates go as far back as 3000 B.C. But pigeons had their biggest moments during the first and second World Wars.

When troops didn’t have access to radio or telephones, they looked to pigeons. Their unique ability to find their way back to the loft, even when taking off from unfamiliar places, became a valuable asset to isolated soldiers. Several of these birds received some of the highest military honors, like a pigeon named G.I. Joe who received the British Dickin medal for bravery for flying through an artillery bombardment in Italy.

After the end of the second World War, a group of these pigeons wound up in Bozeman with their wartime caretaker Dan Corcoran, who served in the United States Army Pigeon Service. Later, Corcoran would help start the Bridger Mountain Racing Pigeon Club.

Corcoran donated several of his Pigeon Corps birds to be bred with racers. And when Dušan picked the sport back up, his first birds were the descendants of those American Army pigeons.

“But then I wanted to try our pigeons from Czechoslovakia. So I imported some pigeons from there and they work really well,” Dušan said.

Soon, the Army pigeon genome met some of Slovakia’s finest. Those birds, the birds he loves and cares for today, are the culmination of thousands of years of champions. The best of the best. The fastest, the most reliable — the birds that lives relied on, mixed with the birds Dusan came to know so well during his childhood in former Czechoslovakia.

”We would be laying on the flat roofs of buildings, eating chicken soup and waiting for pigeons to come,” Dušan said. “When the pigeon was sent to the race, they just put little metal counter marks on the leg with some numbers and codes, and you had to take the metal counter mark and put it in a clock.”

Dušan says the kids would grab those metal bracelets and hop on bikes, speeding towards the town’s sole wooden pigeon clock.

“So we would be carrying this message and we were so proud. I remember biking in the street, you felt like you were delivering some Olympic news. So we were racing while pigeons were racing. So there were just so [many] good times with friends and family around pigeons and the games they play.”

That town, Krivany, Slovakia, doesn’t look too different from the Gallatin Valley with its tree-lined foothills and open valleys. It’s where Dušan lived until 1991, when he left to pursue his career as a wildlife photographer.

“You know, I live on a farm and I basically copy it — that Czechoslovakian way of life where we value land for the ability to grow grass… you gotta have grass, you gotta have water, you gotta have trees for firewood. And then you can have sheep and cows and chickens and pigeons and all the animals. So you kind of copy how you grew up.”

The pigeons weren’t Dušan’s idea, though. His wife, Lorca Smetana, had heard that same story about the rooftop chicken soup and the bikes. So on a day off from building their new house in the Gallatin Valley, she tracked down Manhattan police chief Dave Rewitz, the head of the Bridger Mountain Pigeon Racing Club.

“ I said, ‘I have someone who really is gonna want to meet you,” Lorca Smetana said. “And he said, ‘Well, you should just bring them to our annual meeting.’ And he said, ‘Yep, we'll meet on this date at lunch at this restaurant.’ And I said, ‘Done.’ But I didn't tell Dušan.”

It was a hit.

“And I just talked with them, I said, ‘You guys race pigeons?’ ‘Well, yeah!’ So when I got home the next day, I went to First Interstate Bank and I said, ‘Well, I kind of miscalculated, I need more lumber,” Dušan said.

As their house west of Bozeman went up, so did the pigeon loft. With its racehorse stables and clipboards and breeding roosts. Lorca, who has several different day jobs along caring for her heirloom-variety livestock, got her own crew of white doves and started doing releases for weddings, funerals, and even a divorce once.

“To me, it really felt like a missing piece for him, that it wasn't just something that used to happen. It was something that made him alive. So for me it really felt like a gap that could get filled,” Lorca sad.

There’s a special kind of bond between pigeon racers. Dušan knows. He travels the world as a wildlife photographer and keeps a string of pigeon leg bands in his luggage. He was recently in Morocco for a wild boar hunt.

“I looked on the internet, there were some pigeon guys in Morocco and I visited them and it takes about 20 seconds. As soon as you show up and you show them pigeon bands, you're like a family member,” Dušan said.

Across the sport there’s near-equal dedication. Dušan told the story of a friend who, when signing his wedding certificate, had the perfect breeding pair pop into his mind. So he turned over the paper and jotted down their numbers.

Wrapping up his racing season, Dušan now dedicates his time to caring for the next generation of pigeons. But how about the next generation of racers?

“ We have a new club starting at Great Falls. I got calls and there are four, five, six guys again. I knew before I moved to Montana that there was a club in Great Falls, but those people got old and someone passed away or they didn't have patience. But their kids reached the age of 30, 35 and they wanted to do what they did with their parents when they were kids,” Dušan said.

It’s not quite a bonafide resurgence, but it’s something. For now, though, Dušan will prepare his flock for next year’s spring racing. Some of the best will be paired to breed. Others will drift into quiet retirement, watching the next line of racers fumble about the skies above.